Jamie Fox, principal analyst with leading agency Interact Analysis, has over 15 years experience in market intelligence covering components for commercial vehicles including electric vehicles. Here, he considers the crucial electric powertrain differentials for off-highway

***

Having written multiple reports on both off-road and on-road powertrains, I’m now, as we launch our latest Off-Highway Powertrain report, in a good position to reflect on the differences. On a very broad level there are many similarities. For example, over time the market will steadily replace diesel with alternative powertrains, the trend in new technologies is not towards hybrid vehicles in either off-road or on-road, and charging/refuelling infrastructure remains a significant problem that is difficult to solve. Similar competitors, such as Dana, Bosch and Ballard, operate in both markets, and nickel manganese cobalt (NMC) and lithium-ion phosphate (LFP) batteries are dominant in both areas.

However, dig a little deeper and you will see some significant differences between off-road and on-road powertrains that component suppliers, OEMs, and others need to be aware of.

Diversity of off-road market

If you have a product that can be used in a medium-duty truck, it isn’t difficult to adapt it (or create a new product) for a heavy-duty truck. The powertrain of a distribution truck is very similar to a long-haul truck of a given size. If necessary, you could use exactly the same or a very similar powertrain for both purposes. Intercity buses/coaches are a different design to urban buses, but not dramatically different, and the basic powertrain design and chosen components can be similar.

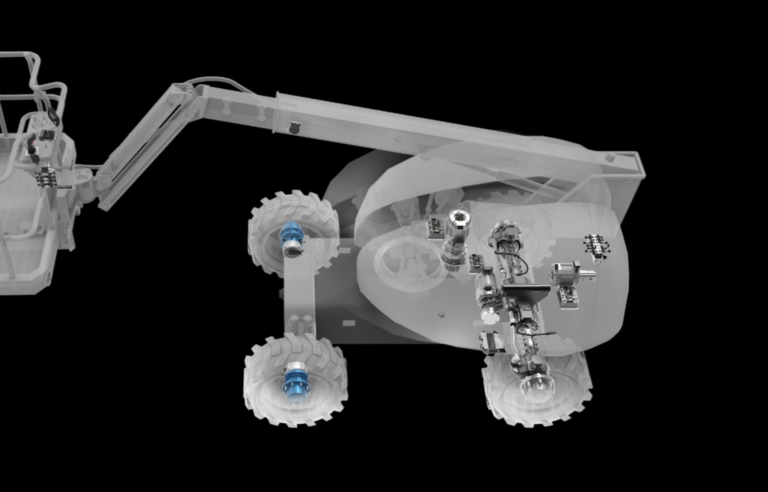

Off-road, with about 6 million vehicles sold in 2022, is similar to the market sizes of trucks and buses (if we include pickup trucks and vans, then trucks is much bigger), but the diversity is much greater. The off-road sector covers tractors, wheel loaders, backhoe loaders, skidsteer/crawler loaders, bulldozers, aerial work platforms, tractors, combines, telehandlers, hauler-dump trucks and others, each with very different usage requirements and powertrain designs. None of the powertrain components used in a small, hand-operated forklift could be reused in a large excavator.

It certainly isn’t one product fits all. Targeting the off-road market will likely mean finding your niche. A broader strategy requires a variety of different products and working closely with customers on designs. This will take time, energy and money.

Harsher environment

Off-road environments include mines, construction sites and farms which tend to have a lot more dust, dirt and other material in the air. Environments can sometimes be noisy, terrain is less smooth and the range of speed and acceleration requirements can be higher. All this has to be factored into the design of a powertrain and selection of components. Sometimes, this will mean little change to an existing on-road product, or simply a protective cover. More often, a completely different design or even fully customized products may be required.

Dust and dirt are a particular concern for fuel cell systems, which makes their adoption a little more challenging. While the fuel cell does not need to be fundamentally different, it needs better protection from the environment than on-road and more regular changing of filters. JCB has said that fuel cells may not be up to the task for off-road, however further testing from a variety of manufacturers is needed in our view.

Off-road electrification is slower (in heavy vehicles)

It would be strange to visit a truck or bus trade show and find few electric vehicles on display, little discussion on the topic of electrification or low interest in it, but at the ConExpo construction exhibition in March 2023 in Las Vegas for example, very few new electric vehicles were announced.

However, the slow pace of electrification does not mean that suppliers should avoid this market. The volume will come later and it tends to be won by those that invest early. The time to invest in new products or substantially expand existing offerings will vary by company need, existing technology, target region and segment. In practice 2023 or 2024 will be a good time to invest in many cases so that a company’s product availability and customer relationships are able to meet demand and stay ahead of competitors in the middle and second half of the decade.

To clarify, forklifts were already 64% electric in 2022 (including a small amount with fuel cells), scissor lifts were at 89% and boom lifts at 25%. Largely due to these categories, 1.5 million (or 27%) of off-highway vehicles/machines covered by this report were already electric in 2022. However, if we exclude these categories, fully electric vehicles in 2022 did not even reach 0.1%, with 2027’s percentage forecast to be just under 1% and around 5% by 2030. This is a much slower pace than electrification in the truck and bus market.

The graph below compares on-road (trucks of 6 tonnes+ and buses) and off-road (all the categories included in our research except forklift, scissors and boom). The 3% market penetration of on-road electrification in 2021 is forecast to be reached in 2029 in off-road.

Growth in off-road electrification is expected to be slow throughout the decade

Expensive components

Gathering prices for both off-road and on-road has helped me refine the data by cross-checking them against each other, with significant differences in prices between the sectors in many cases making perfect sense.

Unlike the truck market, you cannot produce one motor and then use the same or similar in many different types of off-highway equipment due to the vastly different duty cycles and power and torque requirements, as well as very different sizes of machine. This, combined with the lower volumes in off-highway, means motors and inverters are on average 46% more expensive in off-road per kW, according to the data in our reports.

Our research has also indicated that battery packs in off-highway are 41% more expensive per kWh in off-road than on-road (medium and heavy-duty trucks and buses). For light-duty vehicles, the difference is even larger. Cell cost remains similar but packaging requires more work due to differences in level of robustness, space and reliability. The same modules cannot be reused in more cases.

This varies substantially by application. Forklifts, which can in some cases use lead acid batteries, and have higher volume and commoditization than most off-road vehicles, have an even lower battery price than trucks. In an extreme case, say a very large specialized machine for mining where only 5 or 10 electric units might be produced, the battery pack price per kWh could be more than double the on-road case.

Almost all of the extra cost in an off-road electrified powertrain comes from the battery pack. Fuel cell costs are only slightly higher (due to volume), onboard chargers are only slightly higher as well. DC-DC converters are often less expensive in off-highway, due to the smaller voltage range.

Off-road has less competition – for now

It is rare to see a company specializing only on off-road. Most companies focus on both, or only on-road (for now). For on-road in recent years, we are beginning to hear comments such as “red ocean”, “bloodbath”, “20 companies bidding on the same quote”. In off-road, this is less common. If anything, there seems a clear need for more suppliers to enter the market to help drive innovation and price reductions.

For most trucks and buses (at least within urban environments rather than long distance), BEV is clearly already winning the battle for the future. But off-road there are situations that are fundamentally difficult to do with BEV (such as extremely heavy machines, or those operated for 15+ hours a day). Hydrogen vehicles, both fuel cells and ICE, in theory have more of an opportunity to find niches. That being said, we currently forecast more hydrogen vehicles to be sold in trucks than off-road because of where manufacturers are focusing at the moment. And we also forecast a lot more BEV than hydrogen off-road. But it´s not a done deal. There is a lot to play for.

In 2022, the battery pack accounted for more than half the on-road dollars. It is only 38% in off-road. Based on this empirical evidence, we think the reason in some cases could be the need for higher peak power (meaning more expensive motors and inverters) and a lack of range anxiety (in offroad you are very often near your company site so there is less margin for error required in the battery pack).

E-axles are talked about a lot in on-road. It´s been a hot topic for a couple of years at least. But in off-road, this is not what manufactures are focused on. This is likely due to the different shape and therefore required architecture of off-highway vehicles. Less need for aerodynamic shapes may also be a factor in how components are packaged.

On-road, permanent magnet motors dominate with a little over 90% of the units and revenue. But off-road, our data shows that induction and synchronous reluctance have a role to play with a much larger share.

In conclusion

To summarise, off-road is a harsher, more diverse environment with slower electrification, while on-road has higher volume, more suppliers and lower prices. Both markets offer good opportunities for suppliers.

Our new Off-Road Powertrain report, just published, is now available.